Response to “A More Beautiful Question”

In my time as a science teacher, I have become intimately familiar with humans and our proclivity, or lack thereof, towards questioning. Berger captures something I see constantly: questioning and engagement go hand in hand. I remember a student who asked me why, since ATP is made with Adenine, one of the 4 bases of DNA, TTP, GTP and CTP are not really ever spoken about. While this question may be meaningless to non-biologists, this level of insight is indicative of a true understanding of and engagement with content. The ability to ask sophisticated questions demonstrates knowledge.

In reaction to reading some chapters of Berger's book “A More Beautiful Question” we were asked to participate in a "quickfire" where we wrote down as many questions as we could in 5 minutes in relation to our professional practice. I consider myself lucky as I am always full of questions. In fact, I had a hard time stopping myself once I got on a roll. 29 in total (although to be fair it was 7 minutes not 5).

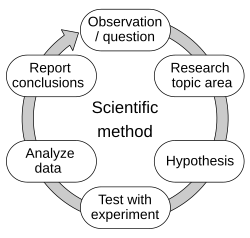

Once my brain gets started on that track I find it pretty easy to keep going. Partially this may explain why I became a science teacher, and more specifically why I chose to study Biology in undergrad. It's no secret, scientists love questions! It's the first step of the scientific method.

The Scientific Method

But reading Berger made me think about how my ability to question isn't shared by everyone around me. This observation led me to two distinct questions I'm still wrestling with:

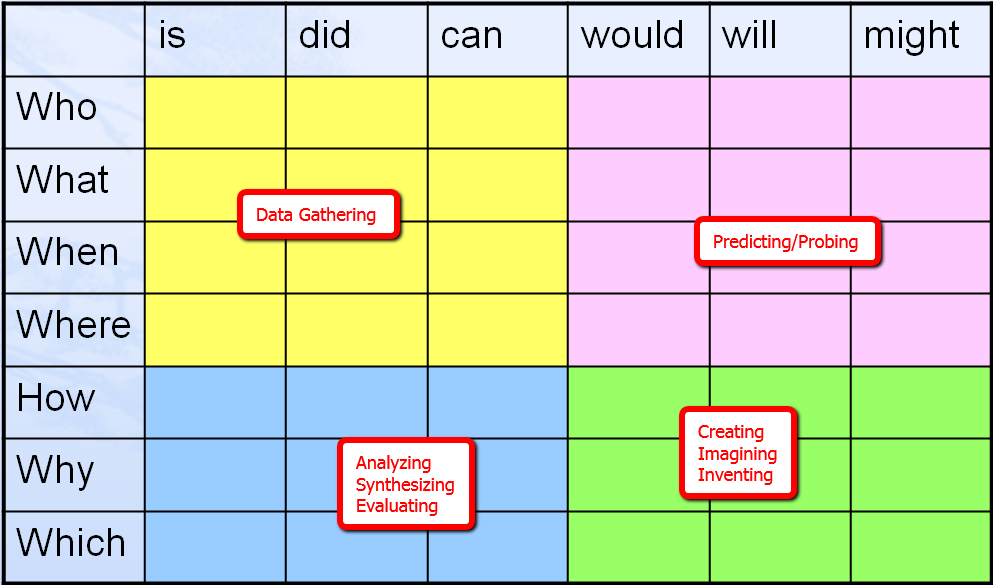

First, why don't other people question the way I do? Berger is right that toddlers ask an astonishing number of questions. I recently spent Christmas with my 3½ year old niece and took great joy in answering her questions, and trying to ask her even stranger questions than she asked me. Yet, Berger is also right that we stop questioning. My husband, who is not as much of a questioner as I am, is often both amused and annoyed when I continuously ask "well, what if X? What if Y?" We have had to come to an agreement that some things are, in fact, not possible, and that when he says so it is not always an invitation to figure out an alternative solution. The same pattern emerges with my students. When I would give them time to ask questions, I would very often get "I don't have any" as a response. One tool that was most helpful was a questioning chart my mentor teacher gave me during my first year of teaching. I printed it and hung it all around the room. When it was time to ask questions, I would prompt students to try to come up with at least one question from each category. Often, the questions were still a little forced but this tool did result in a marked improvement.

Questioning Chart from Canadian School Libraries

Second, reading Berger made me wonder something else entirely. Many of the things he said about questioning and its importance struck me as quite scientific. It made me wonder if "good" questions (and who gets to decide what that is anyways) look the same in all disciplines. A good question in Biology very well might be a bad question in History. This relates to a class that is taught in the program which I teach, the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme. The class is called Theory of Knowledge and it explores ways of knowing in different disciplines. So I am left wondering if the same questioning skills I attempt to foster in my students are valued in other classes as well? And if they do not get answered via the scientific method, how do they get answered? And art! What does a good art question look like? How does one even try to answer an art question?

So I'm left with two questions, and I'm not entirely sure what to do with them yet.

Citations:

Berger, W. (2024). A more beautiful question: The power of inquiry to spark breakthrough ideas (10th ed., rev. & updated). Bloomsbury.